Antihydra: Difference between revisions

Adding sources section, adding a source for its Collatz rule, and documenting access dates of Discord messages based on edit history |

use doi tempate |

||

| (66 intermediate revisions by 13 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{machine|1RB1RA_0LC1LE_1LD1LC_1LA0LB_1LF1RE_---0RA}} | {{machine|1RB1RA_0LC1LE_1LD1LC_1LA0LB_1LF1RE_---0RA}}{{unsolved|Does Antihydra run forever?}} | ||

{{TM|1RB1RA_0LC1LE_1LD1LC_1LA0LB_1LF1RE_---0RA|undecided}}, called '''Antihydra''', is a [[BB(6)]] [[Cryptid]]. Its pseudo-random behaviour was first reported [https://discord.com/channels/960643023006490684/1026577255754903572/1256223215206924318 on Discord] by mxdys on 28 June 2024, and Racheline discovered the high-level rules soon after. It was named after the 2-state, 5-symbol [[Turing machine]] called [[Hydra]] for sharing many similarities to it.<ref>[https://discord.com/channels/960643023006490684/960643023530762341/1257053002859286701 Discord conversation where the machine was named]</ref> | |||

Antihydra is known to not generate Sturmian words<ref>DUBICKAS A. ON INTEGER SEQUENCES GENERATED BY LINEAR MAPS. ''Glasgow Mathematical Journal''. 2009;51(2):243-252. {{doi|10.1017/S0017089508004655}}</ref> (Corollary 4). | |||

<table style="margin: auto; text-align: center;"><tr><td style="width: 200px;">[[File:Antihydra-depiction.png|200px]]<br>Artistic depiction of Antihydra by Jadeix</td><td> </td><td> | |||

{|class="wikitable" style="margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;" | |||

! !!0!!1 | |||

<math display="block">\begin{array}{ | |- | ||

!A | |||

|1RB | |||

|1RA | |||

|- | |||

!B | |||

|0LC | |||

|1LE | |||

|- | |||

!C | |||

|1LD | |||

|1LC | |||

|- | |||

!D | |||

|1LA | |||

|0LB | |||

|- | |||

!E | |||

|1LF | |||

|1RE | |||

|- | |||

!F | |||

| --- | |||

|0RA | |||

|} | |||

The transition table of Antihydra. | |||

</td><td> </td><td>[[File:Antihydra_state_diagram.png|200x200px]] | |||

State diagram of Antihydra | |||

</td><td> </td><td style="width: 220px;">[[File:Antihydra award.jpg|220px]]<br>A community trophy - to be awarded to the first person or group who solves the Antihydra problem | |||

</td><td> </td><td>[[File:Nico-BB-vs-Antihydra.jpg|thumb|A brave busy beaver confronts the dreaded Antihydra. Copyright [https://www.nicoroper.com/ Nico Roper].]]</td></tr></table> | |||

== Analysis == | |||

Let <math>A(a,b):=0^\infty\;1^a\;0\;1^b\;\textrm{E}\textrm{>}\;0^\infty</math>. Then,<ref name="bl">S. Ligocki, "[https://www.sligocki.com/2024/07/06/bb-6-2-is-hard.html BB(6) is Hard (Antihydra)]" (2024). Accessed 22 July 2024.</ref> | |||

<math display="block">\begin{array}{|lll|}\hline | |||

A(a,2b)& \xrightarrow{2a+3b^2+12b+11}& A(a+2,3b+2),\\ | |||

A(0,2b+1)&\xrightarrow{3b^2+9b-1}& 0^\infty\;\textrm{<}\textrm{F}\;110\;1^{3b}\;0^\infty,\\ | |||

A(a+1,2b+1)&\xrightarrow{3b^2+12b+5}& A(a,3b+3).\\\hline | |||

\end{array}</math> | \end{array}</math> | ||

< | <div class="toccolours mw-collapsible mw-collapsed">'''Proof'''<div class="mw-collapsible-content"> | ||

Consider the partial configuration <math>P(m,n):=0\;1^m\;\textrm{E}\textrm{>}\;0\;1^n\;0^\infty</math>. The configuration after two steps is <math>0\;1^{m-1}\;0\;\textrm{A}\textrm{>}\;1^{n+1}\;0^\infty</math>. We note the following shift rule: | |||

<math display="block">\begin{array}{|c|}\hline\textrm{A}\textrm{>}\;1^s\xrightarrow{s}1^s\;\textrm{A}\textrm{>}\\\hline\end{array}</math> | |||

As a result, we get <math>0\;1^{m-1}\;0\;1^{n+1}\;\textrm{A}\textrm{>}\;0^\infty</math> after <math>n+1</math> steps. Advancing two steps produces <math>0\;1^{m-1}\;0\;1^{n+2}\;\textrm{<}\textrm{C}\;0^\infty</math>. A second shift rule is useful here: | |||

<math display="block">\begin{array}{|c|}\hline1^s\;\textrm{<}\textrm{C}\xrightarrow{s}\textrm{<}\textrm{C}\;1^s\\\hline\end{array}</math> | |||

This allows us to reach <math>0\;1^{m-1}\;0\;\textrm{<}\textrm{C}\;1^{n+2}\;0^\infty</math> in <math>n+2</math> steps. Moving five more steps gets us to <math>0\;1^{m-2}\;\textrm{E}\textrm{>}\;0\;1^{n+3}\;0^\infty</math>, which is the same configuration as <math>P(m-2,n+3)</math>. Accounting for the head movement creates the condition that <math>m\ge 4</math>. In summary: | |||

<math display="block">\begin{array}{|c|}\hline P(m,n)\xrightarrow{2n+12}P(m-2,n+3)\text{ if }m\ge 4.\\\hline\end{array}</math> | |||

With <math>A(a,b)</math> we have <math>P(b,0)</math>. As a result, we can apply this rule <math display="inline">\big\lfloor\frac{1}{2}b\big\rfloor-1</math> times (assuming <math>b\ge 4</math>), which creates two possible scenarios: | |||

#If <math>b\equiv0\ (\operatorname{mod}2)</math>, then in <math>\sum_{i=0}^{(b/2)-2}(2\times 3i+12)=\textstyle\frac{3}{4}b^2+\frac{3}{2}b-6</math> steps we arrive at <math display="inline">P\Big(2,\frac{3}{2}b-3\Big)</math>. The matching complete configuration is <math>0^\infty\;1^a\;011\;\textrm{E}\textrm{>}\;0\;1^{(3b)/2-3}\;0^\infty</math>. After <math>3b+4</math> steps this is <math>0^\infty\;1^a\;\textrm{<}\textrm{C}\;00\;1^{(3b)/2}\;0^\infty</math>, which then leads to <math>0^\infty\;\textrm{<}\textrm{C}\;1^a\;00\;1^{(3b)/2}\;0^\infty</math> in <math>a</math> steps. After five more steps, we reach <math>0^\infty\;1\;\textrm{E}\textrm{>}\;1^{a+2}\;00\;1^{(3b)/2}\;0^\infty</math>, from which another shift rule must be applied:<math display="block">\begin{array}{|c|}\hline\textrm{E}\textrm{>}\;1^s\xrightarrow{s}1^s\;\textrm{E}\textrm{>}\\\hline\end{array}</math>Doing so allows us to get the configuration <math>0^\infty\;1^{a+3}\;\textrm{E}\textrm{>}\;00\;1^{(3b)/2}\;0^\infty</math> in <math>a+2</math> steps. In six steps we have <math>0^\infty\;1^{a+2}\;011\;\textrm{E}\textrm{>}\;1^{(3b)/2}\;0^\infty</math>, so we use the shift rule again, ending at <math>0^\infty\;1^{a+2}\;0\;1^{(3b)/2+2}\;\textrm{E}\textrm{>}\;0^\infty</math>, equal to <math display="inline">A\Big(a+2,\frac{3}{2}b+2\Big)</math>, <math display="inline">\frac{3}{2}b</math> steps later. This gives a total of <math display="inline">2a+\frac{3}{4}b^2+6b+11</math> steps. | |||

#If <math>b\equiv1\ (\operatorname{mod}2)</math>, then in <math display="inline">\frac{3}{4}b^2-\frac{27}{4}</math> steps we arrive at <math display="inline">P\Big(3,\frac{3b-9}{2}\Big)</math>. The matching complete configuration is <math>0^\infty\;1^a\;0111\;\textrm{E}\textrm{>}\;0\;1^{(3b-9)/2}\;0^\infty</math>. After <math>3b+2</math> steps this becomes <math>0^\infty\;1^a\;\textrm{<}\textrm{F}\;110\;1^{(3b-3)/2}\;0^\infty</math>. If <math>a=0</math> then we have reached the undefined <code>F0</code> transition with a total of <math display="inline">\frac{3}{4}b^2+3b-\frac{19}{4}</math> steps. Otherwise, continuing for six steps gives us <math>0^\infty\;1^{a-1}\;0111\;\textrm{E}\textrm{>}\;1^{(3b-3)/2}\;0^\infty</math>. We conclude with the configuration <math>0^\infty\;1^{a-1}\;0\;1^{(3b+3)/2}\;\textrm{E}\textrm{>}\;0^\infty</math>, equal to <math display="inline">A\Big(a-1,\frac{3b+3}{2}\Big)</math>, in <math display="inline">\frac{3b-3}{2}</math> steps. This gives a total of <math display="inline">\frac{3}{4}b^2+\frac{9}{2}b-\frac{1}{4}</math> steps. | |||

The information above can be summarized as | |||

<math display="block">A(a,b)\rightarrow\begin{cases}A\Big(a+2,\frac{3}{2}b+2\Big)&\text{if }b\ge 2,b\equiv0\pmod{2};\\0^\infty\;\textrm{<}\textrm{F}\;110\;1^{(3b-3)/2}\;0^\infty&\text{if }b\ge3,b\equiv1\pmod{2},\text{ and }a=0;\\A\Big(a-1,\frac{3b+3}{2}\Big)&\text{if }b\ge3,b\equiv1\pmod{2},\text{ and }a>0.\end{cases}</math> | |||

Substituting <math>b\leftarrow 2b</math> for the first case and <math>b\leftarrow 2b+1</math> for the other two yields the final result. | |||

</div></div> | |||

In effect, the halting problem for Antihydra is about whether repeatedly applying the function <math display="inline">f(n)=\Big\lfloor\frac{3n}{2}\Big\rfloor+2</math> will at some point produce more odd values of <math>n</math> than twice the number of even values. | |||

These rules can be modified to use the function <math display="inline">H(n)=\Big\lfloor\frac{3n}{2}\Big\rfloor</math>, or the [[Hydra function]], which strengthens Antihydra's similarities to Hydra. In this variant of the sequence, each value is shifted up by 4, including the initial one. This keeps parity of the original, yet the terms can now be related using <math>H</math>: | |||

<math display="block">H^i(8)=f^i(4)+4</math> | |||

where superscripts denote iterated application. Here <math>H^i(8)</math> corresponds to the variant sequence and <math>f^i(4)</math> to the original one. | |||

<div class="toccolours mw-collapsible mw-collapsed">'''Proof (trivial)'''<div class="mw-collapsible-content"> | |||

We use the following lemma | |||

<math display="block">\forall n : H(n+4)=f(n)+4</math> | |||

which is clear from the definitions: | |||

<math display="block">\Big \lfloor \frac{3(n+4)}{2} \Big \rfloor = \Big \lfloor \frac{3(n)}{2} \Big \rfloor + 2 + 4</math> | |||

<div class="toccolours mw-collapsible mw-collapsed">'''(Details)'''<div class="mw-collapsible-content"> | |||

<math display="block">\Big \lfloor \frac{3(n+4)}{2} \Big \rfloor</math> | |||

<math display="block">= \Big \lfloor \frac{3(n)+12}{2} \Big \rfloor</math> | |||

<math display="block">= \Big \lfloor \frac{3(n)}{2}+6 \Big \rfloor</math> | |||

<math display="block">= \Big \lfloor \frac{3(n)}{2} \Big \rfloor + 6</math> | |||

<math display="block">= \Big \lfloor \frac{3(n)}{2} \Big \rfloor + 2 + 4</math> | |||

</div></div> | |||

== | The proof is by induction. The base case, <math> H^0(8)=f^0(4)+4 </math> is equivalent to the trivial <math>8=4+4</math>. The induction step is next. Starting from the induction hypothesis: | ||

<math display="block">H^i(8)=f^i(4)+4</math> | |||

<math display="block">H(H^i(8))=H(f^i(4)+4)</math> | |||

Use the lemma: | |||

<math display="block">H(H^i(8))=f(f^i(4))+4</math> | |||

<math display="block">H^{i+1}(8)=f^{i+1}(4)+4</math> | |||

which was to be shown. Thus, for all i <math>\in \mathbb{N}</math>: | |||

<math display="block">H^i(8)=f^i(4)+4</math> | |||

</div></div> | |||

== Trajectory == | |||

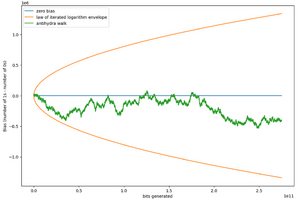

[[File:Antihydra Walk.png|thumb|Path of parity of repeated applications of Hydra map for Antihydra.]] | |||

Starting from a blank tape, Antihydra reaches <math>A(0, 4)</math> in 11 steps and then the rules are repeatedly applied. So far, Antihydra has been simulated to <math>2^{38}</math> rule steps,<ref>https://discord.com/channels/960643023006490684/1026577255754903572/1271528180246773883</ref> at which point <math>a</math> exceeds <math>2^{37}</math>. Here are the first few: | |||

<math display="block">\begin{array}{|c|}\hline A(0,4)\xrightarrow{47}A(2,8)\xrightarrow{111}A(4,14)\xrightarrow{250}A(6,23)\xrightarrow{500}A(5,36)\xrightarrow{1209}A(7,56)\xrightarrow{2713}A(9,86)\rightarrow\cdots\\\hline\end{array}</math> | |||

The trajectory of <math>a</math> values resembles a random walk in which the walker can only move in step sizes +2 or -1 with equal probability, starting at position 0. If <math>P(n)</math> is the probability that the walker will reach position -1 from position <math>n</math>, then it can be seen that <math display="inline">P(n)=\frac{1}{2}P(n-1)+\frac{1}{2}P(n+2)</math>. Solutions to this recurrence relation come in the form <math display="inline"> P(n)=c_0{\left(\frac{\sqrt{5}-1}{2}\right)}^n+c_1+c_2{\left(-\frac{1+\sqrt{5}}{2}\right)}^n</math>, which after applying the appropriate boundary conditions reduces to <math display="inline">P(n)={\left(\frac{\sqrt{5}-1}{2}\right)}^{n+1}</math>. This means that if the walker were to get to the position of the current <math>a</math> value, then the probability of it ever reaching position -1 is less than <math display="inline">{\left( \frac{\sqrt{5}-1}{2} \right)}^{2^{37}}\approx 2.884\times 10^{-28723042565}</math>. This combined with the fact that the expected position of the walker after <math>k</math> steps is <math display="inline">\frac{1}{2}k</math> strongly suggests Antihydra [[probviously]] runs indefinitely. | |||

== Code == | |||

The following Python program implements the abstracted behavior of the Antihydra. Proving whether it halts or not would also solve the Antihydra problem:<syntaxhighlight lang="python" line="1"> | |||

# Current value of the iterated Hydra function starting with initial value 8 (the values do not overflow) | |||

h = 8 # 4 shifted by 4. | |||

# (Collatz-like) condition counter that keeps track of how many odd and even numbers have been encountered | |||

c = 0 | |||

# If c equals -1 there have been (strictly) more than twice as many odd as even numbers and the program halts | |||

while c != -1: | |||

# If h is even, add 2 to c so even numbers count twice | |||

if h % 2 == 0: | |||

c += 2 | |||

else: | |||

c -= 1 | |||

# Add the current hydra value divided by two (integer division, rounding down) to itself (Hydra function, instead of Antihydra) | |||

# Note that integer division by 2 is equivalent to one bit shift to the right (h >> 1) | |||

h += h//2 | |||

</syntaxhighlight> | |||

The variable values of this iteration have been put into the On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences (OEIS): | |||

* Hydra function values with Antihydra's starting value 8: https://oeis.org/A386792 | |||

* Antihydra's condition values: https://oeis.org/A385902 | |||

Fast [[Hydra]]/Antihydra simulation code by Greg Kuperberg (who said it could be made faster using FLINT):<syntaxhighlight lang="python2" line="1"> | |||

# Python script to demonstrate almost linear time hydra simulation | |||

# using fast multiplication. | |||

# by Greg Kuperberg | |||

import time | |||

from gmpy2 import mpz,bit_mask | |||

# Straight computation of t steps of hydra | |||

def simple(n,t): | |||

for s in range(t): n += n>>1 | |||

return n | |||

# Accelerated computation of 2**e steps of hydra | |||

def hydra(n,e): | |||

if e < 9: return simple(n,1<<e) | |||

t = 1<<(e-1) | |||

(p3t,m) = (mpz(3)**t,bit_mask(t)) | |||

n = p3t*(n>>t) + hydra(n&m,e-1) | |||

return p3t*(n>>t) + hydra(n&m,e-1) | |||

def elapsed(): | |||

(last,elapsed.mark) = (elapsed.mark,time.process_time()) | |||

return elapsed.mark-last | |||

elapsed.mark = 0 | |||

return 0 | |||

(n,e) = (mpz(3),25) | |||

elapsed() | |||

print('hydra: steps=%d hash=%016x time=%.6fs' | |||

% (1<<e,hash(hydra(n,e)),elapsed())) | |||

== | # Quadratic time algorithm for comparison | ||

< | # print('simple: steps=%d hash=%016x time=%.6fs' | ||

# % (1<<e,hash(simple(n,1<<e)),elapsed())) | |||

</syntaxhighlight> | |||

==References== | |||

[[Category: | [[Category:BB(6)]][[Category:Cryptids]] | ||

Latest revision as of 16:20, 2 December 2025

1RB1RA_0LC1LE_1LD1LC_1LA0LB_1LF1RE_---0RA (bbch), called Antihydra, is a BB(6) Cryptid. Its pseudo-random behaviour was first reported on Discord by mxdys on 28 June 2024, and Racheline discovered the high-level rules soon after. It was named after the 2-state, 5-symbol Turing machine called Hydra for sharing many similarities to it.[1]

Antihydra is known to not generate Sturmian words[2] (Corollary 4).

Artistic depiction of Antihydra by Jadeix |

The transition table of Antihydra. |

State diagram of Antihydra |  A community trophy - to be awarded to the first person or group who solves the Antihydra problem |  |

Analysis

Let . Then,[3]

Consider the partial configuration . The configuration after two steps is . We note the following shift rule: As a result, we get after steps. Advancing two steps produces . A second shift rule is useful here: This allows us to reach in steps. Moving five more steps gets us to , which is the same configuration as . Accounting for the head movement creates the condition that . In summary: With we have . As a result, we can apply this rule times (assuming ), which creates two possible scenarios:

- If , then in steps we arrive at . The matching complete configuration is . After steps this is , which then leads to in steps. After five more steps, we reach , from which another shift rule must be applied:Doing so allows us to get the configuration in steps. In six steps we have , so we use the shift rule again, ending at , equal to , steps later. This gives a total of steps.

- If , then in steps we arrive at . The matching complete configuration is . After steps this becomes . If then we have reached the undefined

F0transition with a total of steps. Otherwise, continuing for six steps gives us . We conclude with the configuration , equal to , in steps. This gives a total of steps.

The information above can be summarized as Substituting for the first case and for the other two yields the final result.

In effect, the halting problem for Antihydra is about whether repeatedly applying the function will at some point produce more odd values of than twice the number of even values.

These rules can be modified to use the function , or the Hydra function, which strengthens Antihydra's similarities to Hydra. In this variant of the sequence, each value is shifted up by 4, including the initial one. This keeps parity of the original, yet the terms can now be related using : where superscripts denote iterated application. Here corresponds to the variant sequence and to the original one.

We use the following lemma which is clear from the definitions:

The proof is by induction. The base case, is equivalent to the trivial . The induction step is next. Starting from the induction hypothesis:

Use the lemma: which was to be shown. Thus, for all i :

Trajectory

Starting from a blank tape, Antihydra reaches in 11 steps and then the rules are repeatedly applied. So far, Antihydra has been simulated to rule steps,[4] at which point exceeds . Here are the first few: The trajectory of values resembles a random walk in which the walker can only move in step sizes +2 or -1 with equal probability, starting at position 0. If is the probability that the walker will reach position -1 from position , then it can be seen that . Solutions to this recurrence relation come in the form , which after applying the appropriate boundary conditions reduces to . This means that if the walker were to get to the position of the current value, then the probability of it ever reaching position -1 is less than . This combined with the fact that the expected position of the walker after steps is strongly suggests Antihydra probviously runs indefinitely.

Code

The following Python program implements the abstracted behavior of the Antihydra. Proving whether it halts or not would also solve the Antihydra problem:

# Current value of the iterated Hydra function starting with initial value 8 (the values do not overflow)

h = 8 # 4 shifted by 4.

# (Collatz-like) condition counter that keeps track of how many odd and even numbers have been encountered

c = 0

# If c equals -1 there have been (strictly) more than twice as many odd as even numbers and the program halts

while c != -1:

# If h is even, add 2 to c so even numbers count twice

if h % 2 == 0:

c += 2

else:

c -= 1

# Add the current hydra value divided by two (integer division, rounding down) to itself (Hydra function, instead of Antihydra)

# Note that integer division by 2 is equivalent to one bit shift to the right (h >> 1)

h += h//2

The variable values of this iteration have been put into the On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences (OEIS):

- Hydra function values with Antihydra's starting value 8: https://oeis.org/A386792

- Antihydra's condition values: https://oeis.org/A385902

Fast Hydra/Antihydra simulation code by Greg Kuperberg (who said it could be made faster using FLINT):

# Python script to demonstrate almost linear time hydra simulation

# using fast multiplication.

# by Greg Kuperberg

import time

from gmpy2 import mpz,bit_mask

# Straight computation of t steps of hydra

def simple(n,t):

for s in range(t): n += n>>1

return n

# Accelerated computation of 2**e steps of hydra

def hydra(n,e):

if e < 9: return simple(n,1<<e)

t = 1<<(e-1)

(p3t,m) = (mpz(3)**t,bit_mask(t))

n = p3t*(n>>t) + hydra(n&m,e-1)

return p3t*(n>>t) + hydra(n&m,e-1)

def elapsed():

(last,elapsed.mark) = (elapsed.mark,time.process_time())

return elapsed.mark-last

elapsed.mark = 0

(n,e) = (mpz(3),25)

elapsed()

print('hydra: steps=%d hash=%016x time=%.6fs'

% (1<<e,hash(hydra(n,e)),elapsed()))

# Quadratic time algorithm for comparison

# print('simple: steps=%d hash=%016x time=%.6fs'

# % (1<<e,hash(simple(n,1<<e)),elapsed()))

References

- ↑ Discord conversation where the machine was named

- ↑ DUBICKAS A. ON INTEGER SEQUENCES GENERATED BY LINEAR MAPS. Glasgow Mathematical Journal. 2009;51(2):243-252. doi:10.1017/S0017089508004655

- ↑ S. Ligocki, "BB(6) is Hard (Antihydra)" (2024). Accessed 22 July 2024.

- ↑ https://discord.com/channels/960643023006490684/1026577255754903572/1271528180246773883