1RB1RE_1LC0RA_0RD1LB_---1RC_1LF1RE_0LB0LE

1RB1RE_1LC0RA_0RD1LB_---1RC_1LF1RE_0LB0LE (bbch)

A BB(6) TM which is modeled by

A(a, b) -> A(a-b, 4b+2) if a > b A(a, b) -> A(2a+1, b-a) if a < b A(a, b) -> Halt if a = b Start A(1, 2)

for A(a, b) = 0^inf 10^{a-1} 0 1^b E> 0^inf. The configuration is always valid because is always maintained. Forward simulations of this model by @-d and Andrew Ducharme do not halt after 50,000,000 iterations of the map A(a,b). It is a possible Cryptid since it seems hard to predict whether we could ever end up in A(n, n), but investigations are ongoing on Discord as of 27 Jun 2024. It is the inspiration for the Beaver Math Olympiad.

A Backward Reasoning Approach

An alternative approach is to work backwards and study the points which A(a,b) maps to the line a = b. For example, the points (2,7), (3,25), (4,71), and (5,181) all eventually map to a = b. (2,7) is immediately sent to a = b because, under the a < b rule, (5,181) requires more steps:

How are these points found? It's faster not to consider individual points, but as @Rae identified, the set of lines which are mapped to a = b. Introducing an index , we can rewrite A(a,b) as If , then the lines with slopes map to that line. The two possible slopes are, for and respectively,

and

Indexing m and b themselves, in (slope, y-intercept) space,

.

Iteratively applying this (m,b) map finds an infinite set of points which A sends to a = b. The starting point is said line, with (m, b) = (1,0). Then the two lines of points which map to points on the line (m,b) = (1,0) under a single application A are have slopes and y-intercepts of and (3,1) = (2 + 1, 0 + 1). The four lines of points which map to (1,0) under two applications of A have slopes and y-intercepts and (7,4).

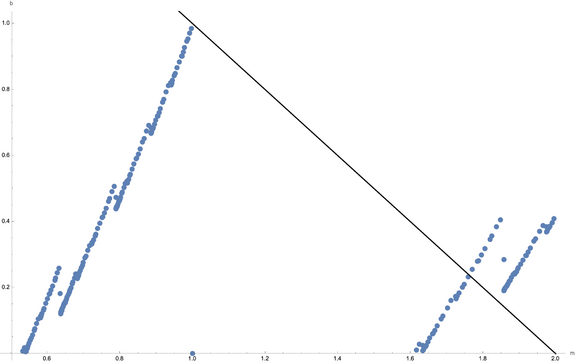

To apply this to the problem at hand, we want to know if any of these generated lines contain the point (1,2), our TM-derived initial condition. The set of all lines (in position space, or (x,y) space) containing (1,2) are described by the line in (m,b) space 2 = m + b. If any of the generated points in (m,b) space sit on 2 = m + b, then the point (x,y) = (1,2) is eventually mapped by A to a point where x = y. In the second image, of (m,b) points after nine iterations, we see there are three possible locations for this to occur.

Location 1: Approaching (m = 1, b= 1) from below

There's two ways to see how (1,1) is not actually an intersection point. First, from Rae, the elementary one: if m > b, m will always be greater than b, so a point where m = b is impossible.

Second, from Andrew, if one wants to generate a point near m = 1, you should create the largest possible value M to swamp out the additive +4 in the denominator of M/(M+4). M can be maximized with n iterations of the (m,b) map by only using the x < y operation. Then apply the x > y operation once for a near-unitary slope. The pair formed by applying the x < y operation n times to (1,0) is . Apply the x > y operation to get

.

Taking the limit as n goes to infinity, we get (1,1), so this TM does not reach the line 2 = m + b here in finite time.

Location 2: Approaching (m = 13/7, b = 4/21) from above

The rightmost possible intersection is the least likely: its approach towards 2 = m + b slows considerably with increasing iterations (because its limit will end up being to above this line). Empirically examining these points, they appear to be near (1.85, 0.19). After 6 through 9 iterations, the closest of the generated (m,b) points to (1.85, 0.19) are (285/151, 37/151), (1117/599, 123/599), (4445/2391, 155/797), and (17757/9559, 1831/9559). Such points are formed by n applications of the (m,b) map when x > y, then two applications of the (m,b) map when x < y, then a single additional application of the x > y and x < y (m,b) maps, in that order. A more concise notation would be .

A closed form equation in n for starting from (1,0) is . Its limit as is , which is safely above 2 = m + b. This strand of points will never cause a halting condition.

Rae showed the same by applying the bounds m > 0 and on the sequence :

Since the combination of operations is empirically determined, this isn't strictly a proof, but the moderate distance of these points from 2 = m + b means the burden of proof isn't that high.

Location 3: Jumping above and below b = m - 2 around m = 1.76...infinitely?

Development of Model from TM Tape

Let f(a,b) represent (10)^a D> 1^b. By inspection, the machine visits f(0,3) f(2,2) f(1,7) f(4,5) f(0,19) f(2,18) f(6,15) f(14,8). I got these rules for f(a,b) and verified them up to 0<=a<=100 and 1<=b<=100. f(a,b) -> f(a-b+1,4b-1) if b < a+2 f(a,a+2) -> halt f(a,b) -> f(2a+2,b-a-1) if b > a+2 I ran these rules from f(0,3) and gave up after reaching a,b > 2^1000000. It looks like halting becomes less and less likely. Is there a way to show this runs forever (or miraculously halts)?

@Shawn Ligocki — 25 Jun 2024 at 11:56 PM ET:

I can confirm roughly the same rules (I chose a slightly different standard config): 1RB1RE_1LC0RA_0RD1LB_---1RC_1LF1RE_0LB0LE E(a, b, c) = 0^inf 10^a 0 10^b 1^c E> 0^inf Base Rules: E(a+1, b, c+2) -> E(a, b+2, c+1) E(a+1, b, 1) -> E(a, 0, 2b+6) E(0, b, c+2) -> E(b+2, 0, c+1) E(0, b, 1) -> Halt(b+4) High-level Rules: E(a, 0, c+1) --> E(a-c-1, 0, 4c+6) if a > c E(a, 0, c+1) --> E(2a+2, 0, c-a) if a < c E(a, 0, c+1) --> Halt(2c+4) if a = c Connecting to your notation @-d : f(a, b+2) -> E(a, 0, b+1)

@Shawn Ligocki — 26 Jun 2024 at 12:25 AM

Hm, this is interesting. I decided to track "spread" akin to what @savask and I have been looking at for the similar 3x3 TM we're looking at in bbxy . Here I define spread = abs(a - c) in config E1(a, c) = E(a, 0, c+1). Here's the results I have so far:

1 E1(2, 0) spread: [2, 2] (0.06s)

100_001 E1(10^6_557, 10^6_555) spread: [1, 10^6_557] (0.44s)

200_001 E1(10^13_124, 10^13_125) spread: [10^6_557, 10^13_125] (1.27s)

300_001 E1(10^19_670, 10^19_669) spread: [10^13_123, 10^19_670] (2.52s)

400_001 E1(10^26_235, 10^26_237) spread: [10^19_668, 10^26_237] (4.23s)

500_001 E1(10^32_799, 10^32_799) spread: [10^26_235, 10^32_799] (6.39s)

600_001 E1(10^39_350, 10^39_352) spread: [10^32_799, 10^39_352] (8.98s)

700_001 E1(10^45_930, 10^45_930) spread: [10^39_350, 10^45_930] (12.06s)

800_001 E1(10^52_486, 10^52_486) spread: [10^45_929, 10^52_486] (15.54s)

900_001 E1(10^59_046, 10^59_047) spread: [10^52_485, 10^59_047] (19.57s)

1_000_001 E1(10^65_613, 10^65_612) spread: [10^59_045, 10^65_613] (24.05s)

1_100_001 E1(10^72_154, 10^72_153) spread: [10^65_609, 10^72_154] (28.92s)

1_200_001 E1(10^78_728, 10^78_729) spread: [10^72_153, 10^78_729] (34.21s)

1_300_001 E1(10^85_288, 10^85_289) spread: [10^78_729, 10^85_289] (40.03s)

1_400_001 E1(10^91_830, 10^91_829) spread: [10^85_288, 10^91_829] (46.40s)

1_500_001 E1(10^98_394, 10^98_393) spread: [10^91_829, 10^98_394] (53.11s)

1_600_001 E1(10^104_961, 10^104_959) spread: [10^98_393, 10^104_961] (60.18s)

1_700_001 E1(10^111_523, 10^111_523) spread: [10^104_958, 10^111_523] (67.75s)

1_800_001 E1(10^118_088, 10^118_088) spread: [10^111_523, 10^118_088] (75.77s)

1_900_001 E1(10^124_631, 10^124_630) spread: [10^118_088, 10^124_631] (84.39s)

2_000_001 E1(10^131_185, 10^131_185) spread: [10^124_630, 10^131_185] (93.41s)

...

3_000_001 E1(10^196_733, 10^196_733) spread: [10^190_163, 10^196_733] (217.87s)

Here spread: [X, Y] means that the spread values (since last print) had min X, max Y

So notice that the spread is basically uniformly increasing. In fact these [X, Y] intervals hardly even overlap!

That makes me think there's something about this that makes small spread impossible (and thus halt impossible)

Or that it's like Bigfoot and it ... could go back to zero, but the chances are infinitesimal!

savask — 26 Jun 2024 at 1:02 AM

Maybe we can simplify a little bit more. Set (a, c) = E(a, 0, c+1) then the rules are (a, c) -> (a-c-1, 4c+5) if a > c (a, c) -> (2a+2, c-a-1) if a < c (a, c) -> Halt if a = c I like that this way they are more symmetrical with a-c-1 vs c-a-1

Shawn Ligocki — 26 Jun 2024 at 2:33 AM

FWIW, there is a value x ~= 1.76 such that as c -> inf: (xc, c) -> (xyc, yc) via path "rll" (right->0 [ie a > c], left->0 [ie a < c], left->0). Which would repeat forever if it were exact, but it is an unstable cycle so any slight deviation and it gets further and further away, so that doesn't seem like a reasonable proof direction :/

dyuan01 — 26 Jun 2024 at 2:32 PM

If we let A(a, c) = (a-1, c-1), we can get these rules: ``` A(a, c) -> A(a-c, 4c+2) if a > c A(a, c) -> A(2a+1, c-a) if a < c A(a, c) -> Halt if a = c ``` And we start with (1, 2) I'm not sure if it even helps, but at least the rules look slightly more "human-manageable"